For Women in Translation Month, we asked our favorite authors and translators share a glimpse into their reading lives with rapid-fire picks for favorite women writers in translation.

Read MoreFrance

Read Julie Orringer's Preface to 'The Boy,' a Novel by Marcus Malte

Marcus Malte’s prize-winning novel The Boy, translated from the French by Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge, is a story that forces us to consider what it means to be human. Beginning in 1908, the narrative starts, quite simply, with the boy, a wild child from the forests of Southern France who sets out, voiceless and innocent, to discover civilization. As he travels between cities and towns, the boy encounters the best and the worst of the world, from ogres and earthquakes, to love and the joys of music, and finally, to war. Malte’s prose is at once poetic and mysterious, and sometimes harsh as he weaves this poignant tale of the human nature.

In her preface to The Boy, Julie Orringer, bestselling author of How to Breathe Underwater, The Invisible Bridge, and The Flight Portfolio, writes: “As we inhabit [the boy] … there is no way to perceive him as other, only as a version of ourselves, at times compassionate, at times violent, always curious, always seeking comfort and love, a balm for what’s been irrevocably lost.” Read Orringer’s full preface below.

The Boy: A Preface by Julie Orringer

Reading The Swiss Family Robinson recently with my eight-year-old son, I came across a passage—amid the ardent shelter-building, tropical-plant identification, animal-shooting, and campfire cookery of the novel’s first chapters—where our narrator, William, expresses the fear that his family’s new home might be inhabited by savages. The author’s (and translator’s) use of the word seemed to require explanation, or context; I asked my son if he knew what it meant.

“I think he means wild animals,” he said. “Beasts.”

I explained, with some discomfort, that the author was actually referring to people, indigenous to the island, who likely lived as hunters and gatherers, employing technology that had been used for thousands of years, and practicing forms of religion, storytelling, dance, dress, and music-making that would have been unfamiliar, and perhaps even frightening, to Europeans. I explained that the word originated with the Latin silva, meaning wood, and silvatica, out of the woods; from this came the French sauvage, and finally our English savage, with its attendant fear of the unknown, of what might lurk in forests, fierce and untameable and possibly intending to do us harm. But why would a person be called a savage, my son still wanted to know; and what made the Swiss family fear them? Underneath his question I sensed another: What is it that makes us recognize one another as human? And what does it mean to be human in the first place?

This subject was much on my own mind because I’d been reading the book you now hold in your hands: Marcus Malte’s brilliant and disturbing novel The Boy, which poses the same question in a different way. Using a trope familiar to literature, one that has long fascinated and perplexed us—from Romulus and Remus abandoned by their mother and nursed by a she-wolf, to the tale of Victor of Aveyron, the eighteenth-century French boy who was discovered after more than a decade on his own in the wild—Malte envisions a man-child, newly orphaned at fourteen, who has lived all his life in the isolated wilds of southern France, with only his nonverbal mother for company; the story opens in the first decade of the twentieth century, on the verge of one of the greatest upheavals of Western history. Notably, the point of view belongs not to some curious observer but—as in T. C. Boyle’s “Wild Child,” or Karen Russell’s “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves”—to the feral child himself, nameless and languageless. As we inhabit him, as we experience his journey into the populated world, there is no way to perceive him as other, only as a version of ourselves, at times compassionate, at times violent, always curious, always seeking comfort and love, a balm for what’s been irrevocably lost. Moving from wilderness to village, from village to town, and from town to city, this extraordinary character perceives, and thereby reveals, the strangeness of the twentieth-century world.

To see every element of our lives (and yes, these are our lives, with only minor differences)—the things we eat, the way we behave towards animals, the way we house and clothe ourselves, the way we worship, speak, make music, treat our children, medicate ourselves, perform the act of love, and wage war—through the eyes of someone to whom all of this is new, constitutes a reevaluation of everything we take for granted. In what ways are we ridiculous, or compassionate, or divine? In what ways are we beastly? Mona Ozouf, president of the Prix Femina jury that awarded its 2016 honor to The Boy, called it, in my imperfect translation, “a novel about, among other things, the ensavagement of human beings by war, which reminds us that barbarism camps on the borders of the civilized world.”

Marcus Malte himself, speculating in an interview about his reasons for choosing the book’s historical setting, said this: “Until now, I’d always located my novels in our own time; I’d described the contemporary world exhaustively, especially its faults, so maybe I’d arrived at a time when this world, our world, weighed on me too much—when I needed to get away from it, at least in my fiction.” But isn't the story of human ensavagement the story of every time? And isn’t the question of what is barbaric or savage in so-called civilization one we have to face in every era? In our own moment, when acts of racial violence and xenophobia have become the stuff of daily news, don’t we need, more than ever, to be reminded of the value of wordless communication, of immersion in nature, of loving touch, of music-making, of empathy, of literature read aloud by one person to another—as well as of the fact that certain wounds, inflicted deeply enough, can never heal?

The book you’re about to read shines a fierce and necessary light on our world. Read it patiently, if you can—a challenge at times, considering the wild and unexpected turns it takes, and the pleasures that lie around every corner—and discover, or re-discover, what it means to be a member of the human tribe.

Order the Book

About the Introducer

Julie Orringer is the author of the novel The Invisible Bridge and the award-winning short-story collection How to Breathe Underwater, which was a New York Times Notable Book. She is the winner of the Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize for Fiction and the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Stanford University, and the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. She lives in Brooklyn.

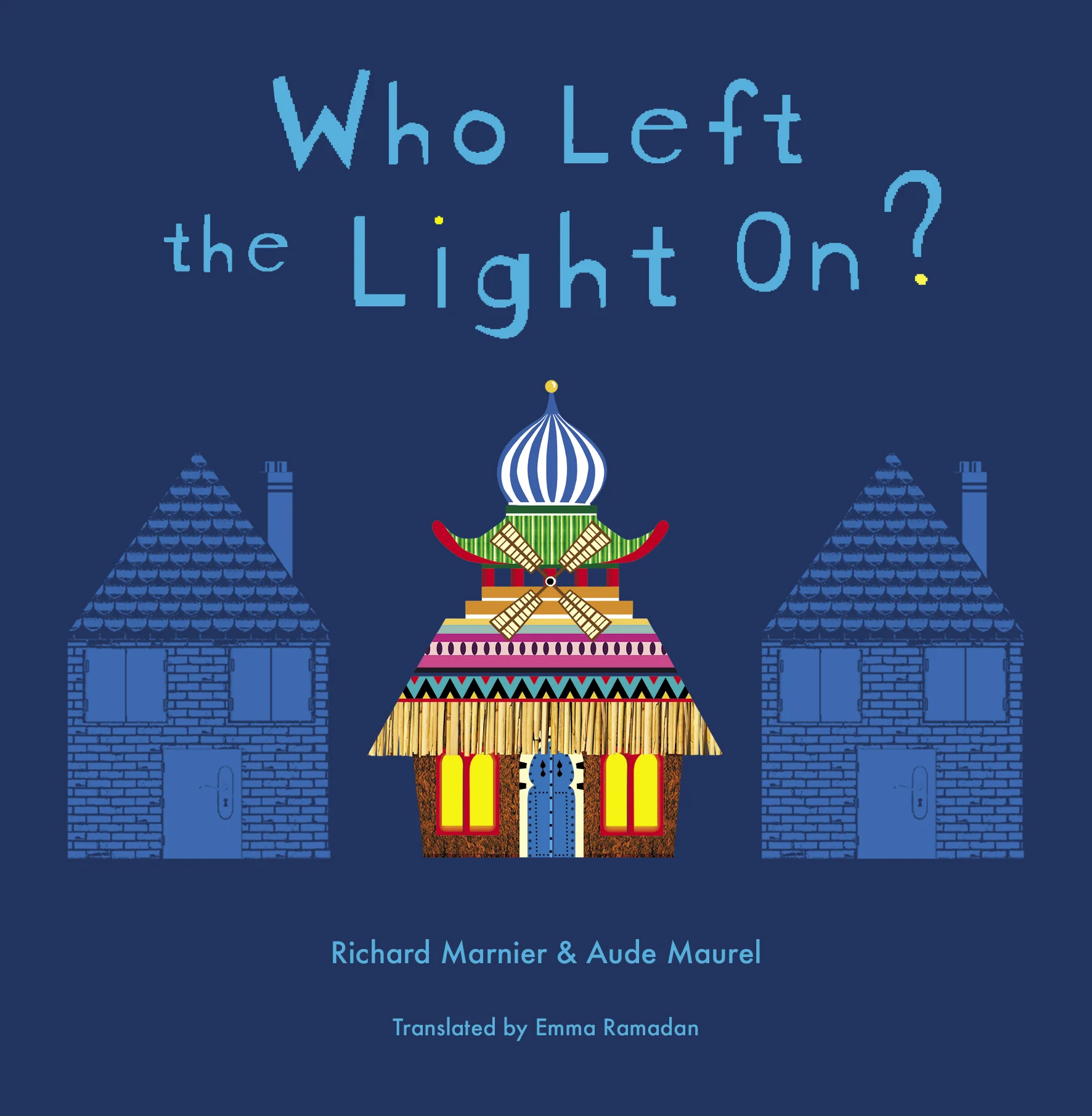

Explore the creative world of Who Left the Light On?

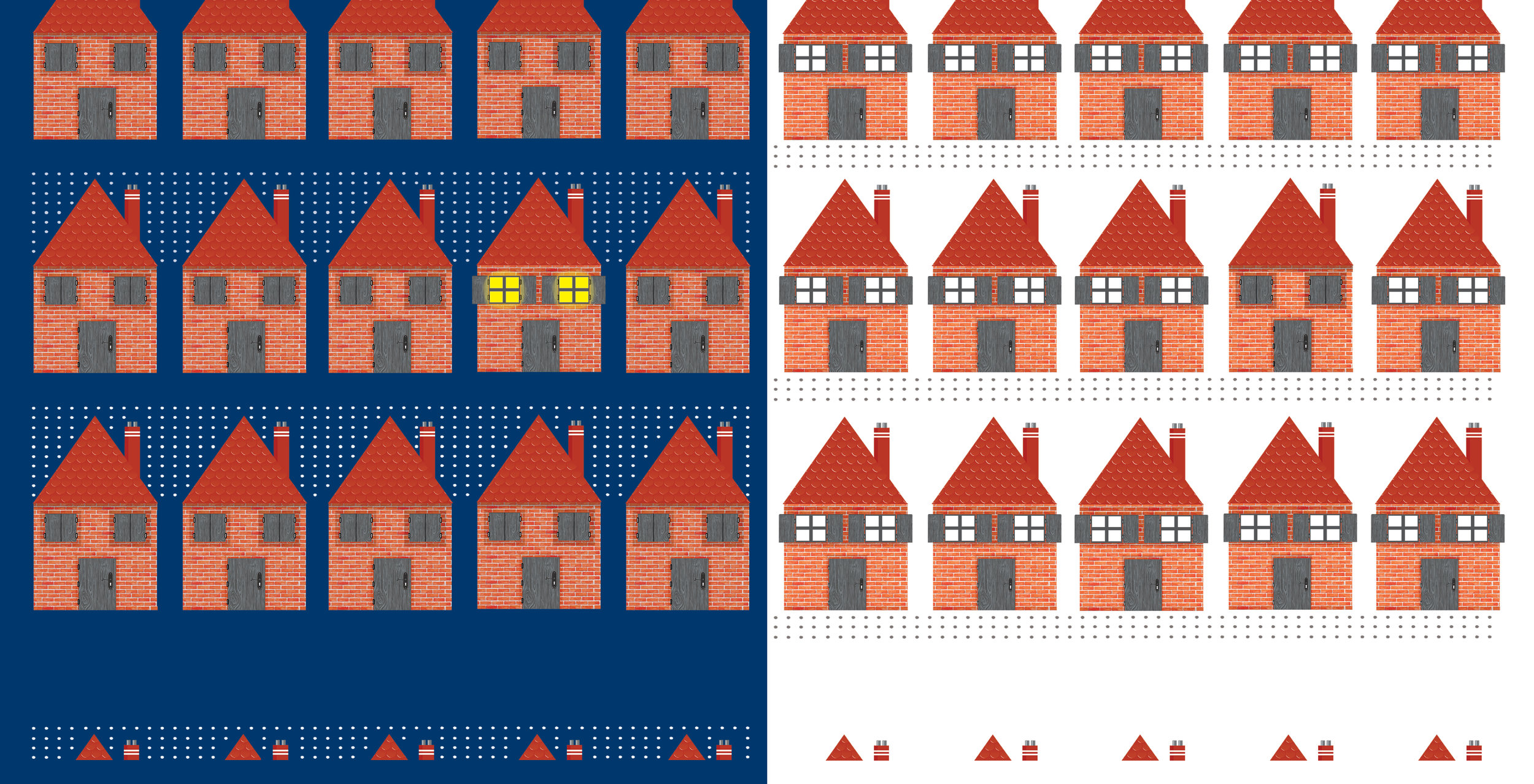

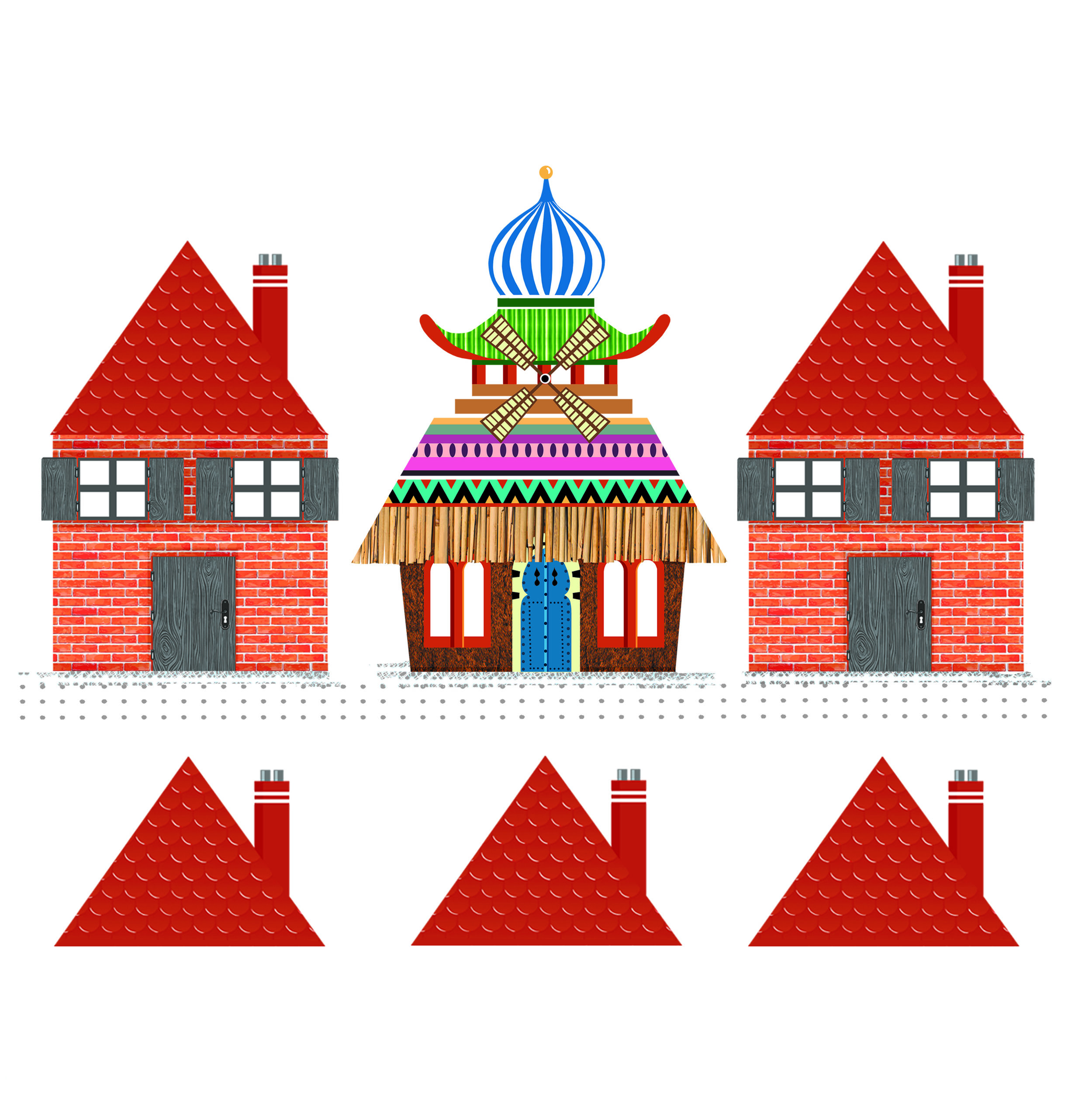

We are thrilled to share some of the captivating illustrations from the first picture book in our Yonder imprint, Who Left the Light On? by Richard Marnier and illustrated by Aude Maurel. Who Left the Light On? is a visually stunning celebration of diversity in a community where creativity is given a free rein and acceptance is the order of the day.

This delightful picture book is about a uniform, monotonous village where all the neighbors follow the same rules of how their homes should look and when it’s okay to turn on the lights—until one day someone decides to turn on the lights at the “wrong” time. This one small act of independence soon shocks others into diverging from the norm and experimenting with their own ideas about design and decor. As the village explodes into color and the neighbors learn to artistically express to their cultural and artistic differences, Marnier’s world will light a spark of empathy and acceptance in young readers.

Artist Aude Maurel’s angular, unvaried images eventually burst into a lively abundance of bamboo huts, shoe-shaped barns, and glitzy palaces—all of which coexist in a state of good-natured neighborly cheer and are sure to enthrall kids and adults alike.

We are especially grateful for the generous support of Katharyn Dawson who sponsored the publication of Who Left the Light On? in honor of her mother’s ninety-fifth birthday. To learn more about sponsoring a Restless book, click here.

By Marcus Malte

Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge

With a Preface by Julie Orringer

Winner of the prestigious Prix Femina, The Boy is an expansive and entrancing historical novel that follows a nearly feral child from the French countryside as he joins society and plunges into the torrid events of the first half of the 20th century.

Paperback • ISBN: 9781632061713

Publication date: Mar 26, 2019