We are delighted to share the 2020 short list for the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing.

Read MoreFiction

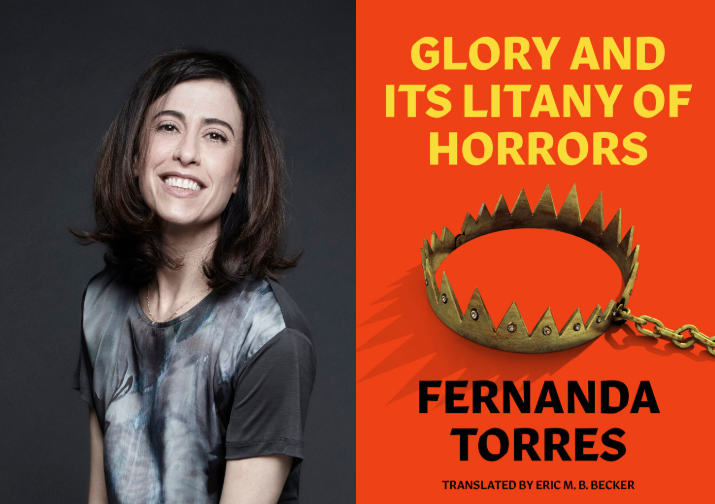

Read an Excerpt from Brazilian Author Fernanda Torres's 'Glory and its Litany of Horrors'

Dear readers,

We loved Brazilian actress Fernanda Torres' delicious debut, The End, hailed for being "an unforgiving portrait of men at their worst." And it’s with sheer delight that we’re bringing you her fitting follow-up: Glory and Its Litany of Horrors, , translated by Words without Borders editor Eric M. B. Becker, a tragicomedy of an actor's downfall from national sex symbol to raging madman. It opens with a performance of King Lear that ends in disaster and closes with a staging of Macbeth behind bars. What happens in between is a vervy, funny, sexy, eye-opening dive into the pleasures and pitfalls of fame, Brazilian style. Read on for an excerpt from the book!

São Paulo. I finally succumbed in São Paulo.

The engineering firm that had sponsored the run decided to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary by inviting its employees to the premiere. In the lobby, before the show, they served a four-cheese pasta with mushrooms, along with some cheap domestic red. Having spent all day hard at work, the guests stuffed themselves with food and alcohol. The curtain was barely up before the first snores echoed across the theater. Since the slightest dramatic pause amplified this Symphony of Morpheus, we began to avoid them as best as we could. We sped through our speaking parts; the faster we rushed through the text, the longer the play dragged on. It was like torture: slow, endless, unbearable. When the lights came up, we patiently waited for half the audience to wake the other so they could reward us for our efforts with yawns and half-hearted applause.

The leading morning newspaper delivered the flogging. A critic ought to have the decency not to show up at the theater on sponsor night, but this one did not. None of them do.

Compared to the São Paulo review, the one that ran in Rio was practically a coronation. On the bottom of page four of the entertainment section, wedged between the comics and the horoscopes, a tiny black-and-white photo of me on all fours embellished the headline: A MIDSUMMER NIGHTMARE. The wise guy began his analysis by listing the actors suffering from delusions of grandeur. I lacked the gravitas for the role of Lear, he decreed, concluding that even Romeo would be a better fit. Regretting I’d not opted for Macbeth, I began to hatch a plan to blow up the newsroom with the wretch inside. He was twenty-eight-years old, the damn upstart, and suffered from the same inferiority complex as all the other journalists working at that newspaper. In barely five paragraphs, he tore everything apart: cast, director, lighting, scenery, costumes; only the Fool, played by Arlindo Correia, escaped the fiasco unscathed. An old theater actor who, like the rest of us, had earned his living on TV, Arlindo had been part of historic productions: he’d worked with Kusnet, Ziembinski, and had belonged to the Teatro de Arena chorus. He shined from the very first reading, he had a knack for switching between irony and tragedy at just the right moment. During rehearsals, I tried to hide the envy of knowing he would come off better than I would—and without the weight of carrying the entire production on his shoulders. I kept my poker face as best I could, until I read the naked truth in that newspaper fancying itself the New York Times. I began to avoid him, I even stopped greeting him. I would arrive at the theater early, mutter an inaudible Hello, and slip into the dressing room practically unnoticed. My only comfort, if you can call it that, was listening to Lineu Castro swear up and down as he arranged his white beard.

Lineu was a marvelous actor, neurotic but marvelous. He had terrible sexual hangups, he’d been a virgin until the age of twenty-eight and must have screwed a woman all of two times in his entire life. One of those times, a child was conceived. Lineu was a hypochondriac and took only occasional showers. No one wanted to share a dressing room with him. We ended up together there in front of the mirror, I listened as he went on and on about how miserable life was with his ugly wife and loser kid. Misfortune had gifted him with a sensibility that was rare in an actor. It wasn’t vanity that moved him but a deep understanding of human pettiness. That’s what led us to cast him in the role of Gloucester, a father betrayed by his bastard son, the villain Edmund, who plots against his legitimate brother, Edgar, in his quest for power.

The torment began one Saturday, fifteen days after the devastating review. I stumbled through my lines during the storm, saving what was left of my voice for the final scene. No one was listening anyway. The cast left the stage with their infamous thunder sheets, I breathed a sigh of relief and was led by Arlindo—the Fool—and Claudio Melo—the Duke of Kent—to the trunk simulating a hut. Lineu and Paulo, Gloucester and Edgar, appeared stage right, a pair of noble pariahs. The young heartthrob Paulo Macedo, an excellent actor no one took seriously because he’d done three soap operas in a row in the same role of idiot, had accepted the challenge, believing the theater would change the course of his career. It did not. He requested a substitute soon after the premiere in São Paulo. He’d been invited to play the lead on a seven o’clock TV series and a lifetime contract compelled him to accept. He was right to do it, because our run came to an end while he was still with us, before we could try out another actor. And even if we had gone on: what chance did Shakespeare stand against the seven o’clock soap?

Paulo and Lineu came on stage in diapers like two Hindu mystics—the costume designer had made them specially for the cliff scene, in which the loyal son rescues his blind father from suicide. Lineu came toward me, groping about, feigning blindness by rolling his eyes back in his head until all you could see were the whites. I worried he’d end up with a detached retina, but he was one of those actors who gave everything to his craft. The duo comes upon the trio composed of Lear, the Fool, and the Duke, lost in the frigid expanse.

That was the moment it all fell apart.

Gloucester comes on stage, carried by Edgar, an anguished expression on the young actor’s face, forced to endure the stench coming from his bathing-averse colleague. We’d made it through a good chunk of the scene when Paulo started in, right on cue, Pillicock sat on Pillicock Hill, Halloo, halloo, loo, loo! and began flapping his wings, imitating a cock as he feigned madness.

I was suddenly beset by an out of body experience.

My spirit left me, admiring from a distance that beautiful young man in his diaper, running around like a winged monkey. How awful it would feel to watch a son humiliate himself like that, I thought. In the audience, those who weren’t asleep also watched aghast. I turned back to poor old Lineu rolling his eyes like he was Carmen Miranda, and I felt pity for Claudio, swimming in his sheepskin stole, sweat pouring down his temples. Stop everything, I begged in silence. Stop the ride, I want to get off.

It was the diapers, the diapers and Lineu feigning blindness, the sickening sight of the young heartthrob covered in his comrade’s bodily fluids, the genius director and his sheet-metal thunder, my failing voice, me on all fours in the cubicle in Copacabana, the heartburn from the chicken, the pervert fireman, the scorched earth reviews, the bewildered audience, the vultures circling the box office, the shopping mall swarming with people chasing winter clearances, my treacherous conscience, the fickle nature of the profession. I focused my attention on the threadbare curtain, I remembered just how much I hated Ivete Maria’s offensive Regan, and I rued my idiotic delusion that I was up to the task of playing Lear. An elderly man in the first row had a coughing fit and his wife opened her purse to fish out a lozenge. The noise of the wrapper layered on to the husband’s spasms, and someone whispered an angry shhhh. The pressure escaped from my diaphragm, the air rose up through my pharynx and paused in my mouth, forcing the upward contraction of my lips. I tried to stifle a laugh. This cold night will turn us all to fools and madmen, Arlindo said; Take heed o' the foul fiend, Paulo continued, and then they both turned to me. I ought to say something, but what? What? I couldn’t even remember what act we were in. I’d totally blanked. I stood there, completely out of character, unable to move. Someone whispered a cue, I tried repeating it, but when I spoke my voice squeaked, choked off by my muffled laughter. You could see the panic stamped across the four idiots’ foreheads. I lost it. Out came the laughter—I couldn’t hold it, couldn’t stop, overcome with a childish, demented, diabolic joy. I feigned madness for a second, I regained the bard’s gravitas, but then it was worse, peals of laughter burst forth with renewed force, filling the auditorium, strong enough to double me over. I put my hands on my knees. I’m sorry, I said, to Lineu, to Paulo, the audience. I’m sorry.

An actor’s imaginary world is a delicate thing. Bent over there in the middle of the action, I looked for a sign, some thought to put an end to my cackling. Debt, the fear of cancer, my disastrous career, the Doctors Without Borders jingle. But the sadistic, inhuman snigger held its ground, indifferent to my appeals to reason. I tried again, more than once—a lead actor has no right to abandon ship—but as soon as I caught sight of the diapers I was plunged back down into the abyss. The curtain, the curtain, I begged. I could hear the murmurs of the audience, the cast rushed to my aid, someone handed me a glass of water. I’ll be fine, I said, I’ll be fine. I steadied my breathing as the rest of the troupe looked on in horror. The audience began to clap in sync, demanding our return. In agony, I appealed to rage, I took a few kung fu leaps, feet and fists flying through the air. It was me against myself. My colleagues gave me some space. I unleashed a primal scream, then another, I exorcized whatever it was as best I could until I regained my senses. I came to a halt, sobered, out of breath. I held it together for two, three, four seconds…. I’m good, I said, I’m good. With a solemn air, I resumed my position at center stage. Lineu, Arlindo, Claudio, and Paulo took their places and I gave the order to open the curtain. The velvet was slowly drawn back, dust dancing in the stage lights, silence awaiting the resumption of the performance. The theater is a beautiful thing.

It lasted all of a second.

Another fit of laughter set in, I have no idea how we made it to the end. And again the next day—I made three attempts, one after the other, the curtain opening and closing as jaws dropped. I stopped the show, I gave the audience their money back, and left the theater still dressed as Lear. That night, sitting in my room at a cheap hotel, the only place willing to swap rooms for tickets, I cried until I had no more tears then passed out. I woke up in a panic, knowing that that very night I would have to face Lineu and Paulo in diapers, and that damn cock. I spent the entire performance in a cold sweat, my belly churning with anxiety. When the storm passed, Claudio and Arlindo led me to the hut and then Paulo came in with Lineu on his back. I tried not to look at the two of them, I delivered my lines facing the other way, but how to cover my ears? Pillicock sat on Pillicock Hill, Halloo, halloo, loo, loo. Another burst of laughter. Another night ruined. Sobs in the dressing room. The problem was becoming chronic. I asked to switch out the costumes, they covered themselves in doublets. That only made matters worse. I couldn’t get the diapers out of my mind. We cut the rooster’s speaking parts, but at that point it was automatic. The minute I sat on the throne, my lungs gave way. It took three weeks and a note in the newspaper before I threw in the towel. The final laugh attack took place before an audience of twenty-two paying customers. I was giggling from the start, completely helpless, and at the slightest provocation. I cut the first act short soon after Ivete Maria declared her deep love for her father. She was absolutely terrible, it was like she was being dubbed. I glanced over at Arlindo, he lowered his head and began to quiver. It was contagious. The curtain came down with the whole cast doubled over laughing, infected with a lack of faith that had begun with me. I went to the hotel to forget it all. In the dark of the hotel room, I didn’t bother to count the drops of anxiety meds I squirted on my tongue, the whole endeavor had left me immune. I lay down on the sagging mattress and planned out my next steps. I would withdraw the money I had in the bank (what was left of my last TV contract), I’d pay what I owed to the team, the fine from the theater, the ads I’d already scheduled, the airfares, I would write a letter to the sponsor accepting responsibility and would go to Brasília to personally offer my mea culpa to the Ministry of Culture. I would give up the profession if I could figure out some other way to make a living. A restaurant, an inn on the coast, who knows, Paraty. Forget it, I thought, tomorrow I’ll figure out what to do with myself. I crashed on the nylon sheets, rocked to sleep by the bard’s words.

Vex not his ghost: O, let him pass! He hates him much

That would upon the rack of this tough world

Stretch him out longer.

That was the end of Laughing Lear.

—from Glory and its Litany of Horrors, by Fernanda Torres, translated from the Portuguese by Eric M. B. Becker

Buy the Book:

About the Author:

Fernanda Torres was born in 1965 in Rio de Janeiro. The daughter of actors, she was raised backstage. Fernanda has built a solid career as an actress and dedicated herself equally to film, theater, and TV since she was 13 years old, and has received many awards, including Best Actress at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival. Over the last twenty years, she has written and collaborated on film scripts and adaptations for theater. She began to write regularly for newspapers and magazines in 2007 and is now a columnist for the newspaper Folha de São Paulo and the magazine Veja-Rio and contributes to the magazine Piauí. Her debut novel, The End, has sold more than 200,000 copies in Brazil. Glory and its Litany of Horrors is her second novel.

About the Translator:

Eric M. B. Becker is a writer, literary translator, and editor of Words without Borders. He is the recipient of fellowships and residencies from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Fulbright Commission, and the Louis Armstrong House Museum. In 2014, he earned a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant for his translation of a collection of short stories from the Portuguese by Neustadt Prize for International Literature winner and 2015 Man Booker International Finalist Mia Couto.. He has also published translations of numerous writers from Brazil, Portugal, and Lusophone Africa. His work has appeared in the New York Times, The Literary Hub, Freeman’s, and Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, among other publications. He has served on the juries of the ALTA National Translation Award and the PEN Translation Prize.

Read Jamaica Kincaid's Introduction to the 300th Anniversary of Robinson Crusoe

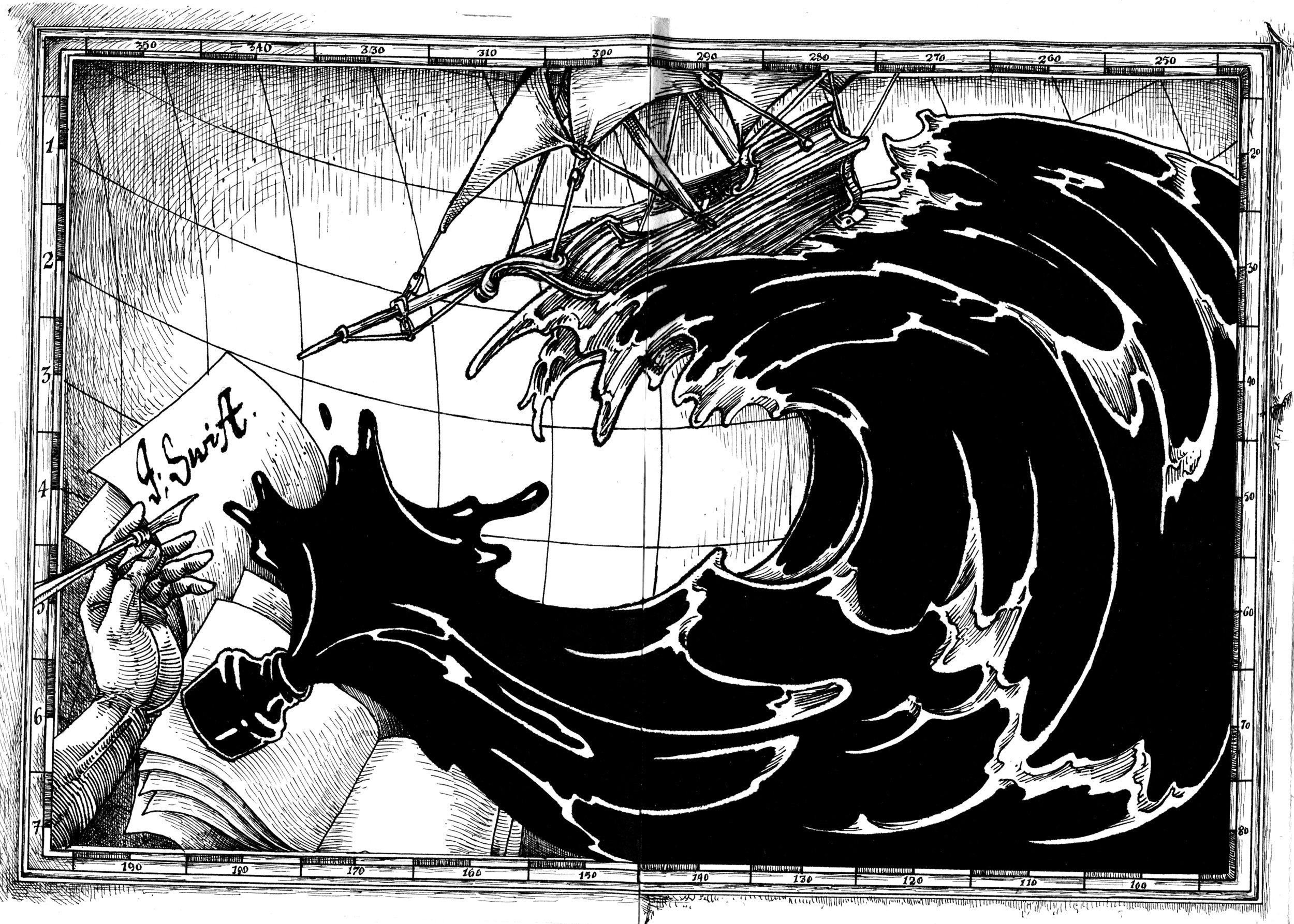

We are thrilled to release a gorgeous new edition of Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe in celebration of the 300th anniversary of its publication. Originally published in 1719, this influential Caribbean adventure story garnered a reputation for being the first great English novel and set the stage for colonial literature as we know it today.

This edition of Robinson Crusoe will further illuminate racial tensions, the current refugee crisis, and existing international conflicts by exposing readers to the analytic voice of Antiguan-Americna author Jamaica Kindcaid. Read Kincaid’s excerpt from the introduction, which begins with “Dear Mr Crusoe, please stay home,” supplemented by Mexican artist Eko’s beautiful illustrations.

INTRODUCTION: JAMAICA KINCAID AND THE STORY OF ROBINSON CRUSOE

Dear Mr Crusoe,

Please stay home. There’s no need for this ruse of going on a trading journey, in which more often than not the goods you are trading are people like me, Friday. There’s no need at all to leave your nice bed and your nice wife and your nice children (everything with you is always nice, except you yourself are not) and hop on a ship that is going to be wrecked in a storm at night (storms like the dark) and everyone (not the cat, not the dog) gets lost at sea except lucky and not-nice-at-all you, and you are near an island that you see in the first light of day and then your life, your real life, begins. That life in Europe was nice, just nice; this life you first see at the crack of dawn is the beginning of your new birth, your new beginning, the way in which you will come to know yourself—not the conniving, delusional thief that you really are, but who you believe you really are, a virtuous man who can survive all alone in the world of a little god-forsaken island. All well and good, but why did you not just live out your life in this place, why did you feel the need to introduce me, Friday, into this phony account of your virtues and your survival instincts? Keep telling yourself geography is history and that it makes history, not that geography is the nightmare that history recounts.

Perhaps it is a mistake to ask someone like me, a Friday if there ever was one, a Friday in all but name, to consider this much loved and admired classic, this book that seems to offer each generation encountering it, sometimes when a child and sometimes as an adult who becomes a child when reading it, the thrill of the adventure of a man being lost at sea, then finding safety on an island that seems to be occupied by nobody, and then making a world that is very nourishing to him physically and spiritually.

I was a ravenous reader as a child. I read the King James version of the Bible so many times that I even came to have opinions early on about certain parts of it (I thought of the Apostle Paul as a tyrant and the New Testament as too much about individuals and not enough about the people); I read everything I could find in the children’s section of the Antigua Public Library, situated on a whole floor just above the Government Treasury. If there was something diabolical or cynical in that arrangement, I never found it, but if it does turn out to be so, I will not be at all surprised. Among the many things that would haunt me were these three books: Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley, and Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. Yes, yes, my early education consisted largely of ignoring that native Europeans were an immoral, repulsive people who were ignorant of most of the other people inhabiting this wonderful earth. Also, they were very good writers, that was true enough.

Read the full introduction on Book Post.

________________________

From the introduction to Robinson Crusoe. Copyright © 2019 by Jamaica Kincaid.

Restless Classics presents the Three-Hundredth Anniversary Edition of Robinson Crusoe, the classic Caribbean adventure story and foundational English novel, with new illustrations by Eko and an introduction by Jamaica Kincaid that recontextualizes the book for our globalized, postcolonial era.

Book Details

Paperback List Price: $19.99 • ISBN: 9781632061195 • Pub. 8/27/2019 • 5.5" x 8.25" • 384 Pages • Fiction: Classics / World Literature / Caribbean / Adventure / Postcolonial Studies • Territory: World • eBook ISBN: 9781632061201

Pre-order from: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Google | Indiebound | iTunes | Kobo

Jamaica Kincaid is a Caribbean American writer whose essays, stories, and novels are evocative portrayals of family relationships and her native Antigua. Settling in New York City when she left Antigua at age 16, she became a staff writer at The New Yorker in 1976. Her books include the short story collection At the Bottom of the River (1983), the novels Annie John (1984) and Lucy (1990), the three-part essay A Small Place (1988), the novel The Autobiography of My Mother (1996) and nonfiction book My Brother (1997). Her “Talk of the Town” columns for The New Yorker were collected in Talk Stories (2001), and in 2005 she published Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya. Her most recent book is the novel See Now Then (2013). She is a professor in the department of African and African American Studies at Harvard University and lives in Vermont.

Born in Mexico in 1958, Eko is an engraver and painter. His wood etchings, often erotic in nature and the focus of controversial discussion, are part of a broader tradition in Mexican folk art popularized by José Guadalupe Posada. He has collaborated on projects for The New York Times, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and the Spanish daily El País, in addition to having published numerous books in Mexico and Spain.

By Fernanda Torres

Translated from the Portuguese by Eric M. B. Becker

2020 Firecracker Award Finalist for Fiction

From Fernanda Torres, the celebrated Brazilian actress and bestselling author of The End, comes a riotous tragicomedy of a famed actor’s path from national sex symbol to cult icon to raving madman after a disastrous performance as King Lear.

Paperback • ISBN: 9781632061126

Publication date: Jul 23, 2019